This leaflet has been written for people who have a personal or family history of breast cancer that could have an inherited cause, and who are considering having a genetic test. It has been written for use with a Clinical Genetics appointment and may answer some of your questions.

Is breast and ovarian cancer inherited?

It is rare for breast and ovarian cancer to be inherited. However, breast cancer occurs in many women, with around one in every seven in the UK developing the disease during their lifetime. Ovarian cancer develops in around one in 50 women in their lifetime. In about 5 - 10% of these cases, a specific gene alteration plays a part. We currently test for 5 genes: BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM and CHEK2 in the R208 test. If any of these genes are altered, that person has a substantially increased risk of developing certain types of cancer, depending on which gene is affected.

What are genes?

Our genes can be found in almost every cell in our body. They are the instructions that enable our bodies to grow and function correctly. BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM and CHEK2 are tumour suppressor genes that help to protect us from developing cancer. An alteration can affect the function of the gene. This can increase the chance of developing, for example, breast, ovarian and prostate cancer, which is more likely to occur at a younger age.

How are these genes inherited?

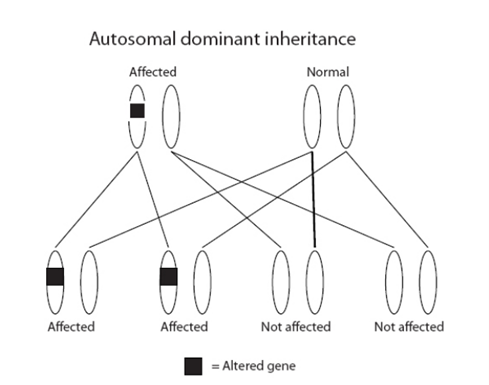

All our genes come in pairs; we inherit one of each pair from our mother and the other from our father. Alterations in the genes in the R208 test are inherited in an ‘autosomal dominant’ manner. This means that the children (male or female) of a person with an alteration in one of these genes have a 1 in 2 (50%) chance of inheriting it. An alteration can be inherited from either parent.

If a person has not inherited an alteration, they cannot pass it on to their children.

Can genetic test results be uncertain?

Sometimes we find an alteration in a gene, but we are not sure of its significance. This is called a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). If we are uncertain whether the gene alteration found is the cause of the cancers in your family, we will not be able to offer a predictive genetic test to other family members. However, we may ask for extra samples from you or other family members to try to gather more information. Often these extra tests help to establish whether or not the VUS is the explanation for your family history of cancer.

What if a relative who has had cancer is not available for testing?

In some cases, where there is no affected family member available for testing we may:

- Offer testing to someone in the family who has not had a cancer. This may be offered if the family history gives a high enough chance that there is a gene alteration. (The relative without cancer must have a 10% chance of having a gene alteration). Testing someone who has not had cancer may make some results harder to interpret. For example, if no gene alteration is found we would not know whether there is a gene alteration that this relative has not inherited or there is another cause for the family history.

- It may be possible to test a tumour sample from a relative who has passed away. Testing tumour samples is more technically difficult than testing a blood sample. It is possible that this test will not work because of the way the tumour samples are stored.

Does everyone who has an alteration in one of these genes get breast cancer?

No. The chance of developing breast and other cancers associated with the genes is not 100%. We do not yet know why some people with an alteration develop cancer and some do not. Lifestyle or other genetic factors are likely to play a role. It is important to note that developing cancer is not the same as dying from cancer. Even if cancer develops, there is a chance that the disease can be cured if it is found and treated early.

What are the genes in the R208 test and the risks associated with them?

BRCA1:

Breast cancer

- Female carriers - 60% to 80%

- Male carriers - 1%

- Members of the general population - 14% (female), 1% (male)

Ovarian cancer

- Female carriers - 40% to 60%

- Male carriers - men do not have ovaries

- Members of the general population - 1% to 2% (female)

Prostate cancer

- Female carriers - women do not have a prostate gland

- Male carriers - minimal increased risk

- Members of the general population - 12%

Pancreatic cancer

- Female carriers - up to 3%

- Male carriers - up to 3%

- Members of the general population - 1.8%

BRCA2:

Breast cancer

- Female carriers - 60% to 80%

- Male carriers - 6%

- Members of the general population - 14% (female), 1% (male)

Ovarian cancer

- Female carriers - 10% to 30%

- Male carriers - men do not have ovaries

- Members of the general population - 1% to 2% (female)

Prostate cancer

- Female carriers - women do not have prostate gland

- Male carriers - 25% (often more aggressive in younger men)

- Members of the general population - 12%

Pancreatic cancer

- Female carriers - 2% to 7%

- Male carriers - 2% to 7%

- Members of the general population - 1.8%

Remember, 10 per cent means one person in every 10 will develop this cancer in their lifetime.

For women who have already been affected with breast cancer, we know there can be an increased chance of developing a completely new cancer. This is different to a cancer which recurs or spreads from the first (original) cancer. Please discuss this with your clinician.

PALB2:

Breast cancer

- Female carriers - 13% to 21% by age 50, 44-63% by age 80

- Male carriers - less than 1% by age 50, around 1% by age 80

- Members of the general population - 14% (female), 1% (male)

Ovarian cancer

- Female carriers - less than 1% by age 50, around 5% by age 80

- Male carriers - men do not have ovaries

- Members of the general population - 1% to 2% (female)

Prostate cancer

- Female carriers - women do not have prostate gland

- Male carriers - minimal increased risk

- Members of the general population - 12%

Pancreatic cancer

- Female carriers - less than 1% by age 50, 2-3% by age 80

- Male carriers - less than 1% by age 50, 2-3% by age 80

- Members of the general population - 1.8%

Family history is taken into account to calculate an individualised risk assessment

ATM:

Breast cancer

- Female carriers - 17% to 30% (Except c.7271T>G which is over 30%)

- Male carriers - minimal increased risk

- Members of the general population - 14% (female), 1% (male)

CHEK2:

Breast cancer

- Female carriers - around 25%

- Male carriers - minimal increased risk

- Members of the general population - 14% (female), 1% (male)

What are the implications of the R208 test?

This testing can sometimes tell you that your chance of developing cancer is increased, but we cannot tell you for certain when, or even if, you will develop cancer.

If an alteration is found in any of the genes in the panel, there is an increased chance of developing cancer. Some people may worry that genetic testing will affect insurance prospects (for example, health, life, or disability insurance). Currently, the insurance industry cannot ask about genetic testing for most policies. This position may change in the future.

Some people feel a range of emotions when they are told that they have a gene alteration which increases their chance of cancer. They may feel angry, shocked, anxious or guilty about the possibility of passing the gene alteration on to their children. Some people may also feel guilty if they do not have the gene alteration when other close relatives do.

Genetic testing in a family can affect other family members, who may need to be told that they too are at an increased risk of developing cancer and may be eligible for genetic testing and/or screening. Different family members may have different reactions to this information, and genetic testing may therefore affect relationships within families. Your clinician will provide you with a letter that you can pass onto relatives to help them to access genetic testing.

Can having a BRCA1 or 2 gene alteration affect cancer treatment?

There are new drugs available called PARP inhibitors (Olaparib and Niraparib) which have been shown to improve survival in individuals diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer who have a BRCA1 or 2 gene alteration. PARP inhibitors are not currently used for carriers of PALB2, ATM or CHEK2.

What screening is available for women with alterations identified through the R208 test?

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

Breast MRI is the most effective form of breast screening for younger women. Breast MRI is offered to women with a BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 or ATM c.7271T>G gene alteration every year from 30 until 49 years of age. Women who have a 50% or 1 in 2 chance of having these specific gene alterations are also eligible for this screening.

Mammography

This form of screening has not been proven to be effective in women under the age of 40. It has been shown to be beneficial over the age of 40, especially alongside breast MRI.

Women with a BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 or ATM c.7271T>G gene alteration are offered annual mammograms from 40 until 69 years of age. Women who have a 50% or 1 in 2 chance of having these specific gene alterations are also eligible for this screening.

Women with a CHEK2 or any other ATM gene alteration are offered annual mammograms from 40 until 49 years of age. They are then enrolled into the NHS breast screening programme to have mammograms every 3 years from 50-69 years of age.

From 70 years of age, women can request to have a mammogram every three years by contacting their local breast unit or GP.

Is there any screening for ovarian cancer?

Some recent evidence suggests that ovarian cancer may help to detect ovarian cancer at an earlier stage. However, there is not enough evidence yet that this screening saves lives. Therefore, it is not currently offered as part of NHS treatment.

Is there any other recommended screening?

If you have a family history of pancreatic cancer, you could talk to your clinician about whether or not pancreatic screening is an option for you.

Having an alteration in one of the genes on the R208 test may be associated with increased risks of developing other types of cancer. The risks of these are likely to be small and there is no additional screening recommended currently.

Risk reducing breast surgery (risk reducing bilateral mastectomy)

This is the surgical removal of healthy breasts to prevent a cancer developing. This has been shown to reduce the chance of developing breast cancer by 90-99%. It does not remove all the risk, as the surgery cannot remove every breast cell. It is a major operation that can have serious complications, so it requires careful consideration. This is only available to women whose lifetime risk of developing breast cancer exceeds 30%.

Risk reducing removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (risk reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy)

This is the surgical removal of healthy ovaries and fallopian tubes to prevent cancer developing, which reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 95%. There is still a small chance of an ovarian-like cancer developing in the surrounding tissue that is left. This is estimated to be between 2 to 5% in a lifetime. In some circumstances, this may also help to reduce the risk of breast cancer if carried out before the natural menopause. Having ovaries removed will start an immediate menopause. Therefore it may be appropriate to have some form of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) until 50 years of age. HRT may not be recommended for women who have had hormone receptor positive breast cancer.

Is there any medication which can reduce the risk of developing breast cancer?

Taking certain medications for five years has been shown to reduce the risk of breast cancer in women at increased risk. Tamoxifen can be offered prior to the menopause, or Raloxifene and Anastrazole after the menopause. These drugs are associated with side effects. Please ask your clinician if interested, and/or see our separate chemoprevention leaflet.

Symptom awareness

We also recommend breast and ovarian cancer awareness for women, and breast and prostate awareness for men. Your clinician will provide you with the relevant booklets from Macmillan with more information about this. Alternatively, there is more information online at www.macmillan.org.uk. These booklets also include information about lifestyle factors which can help to reduce cancer risk in general.

What screening is available for men with alterations identified through the R208 test?

There is currently no national screening programme for prostate cancer in the UK. This is because it has not been proven that the benefits outweigh the risks. Instead of a national screening programme, there is an informed choice programme called prostate cancer risk management. The PSA test is a blood test to help detect prostate cancer. It measures the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in your blood. This is available to healthy men aged 50 or over, who ask their GP about PSA testing. It aims to give men good information about the pros and cons of the PSA test.

BRCA2

Given the increased risk, men with a BRCA2 alteration can be referred to a Urologist to discuss the option of prostate screening in more detail. Currently prostate screening involves measuring PSA levels, but may also involve an initial MRI.

BRCA1, PALB2, ATM and CHEK2

The risk of developing prostate cancer is not greatly increased. Therefore, prostate screening is not currently offered to men with these gene alterations, although they could discuss with their GP about prostate cancer risk management.

Are there any options for people with an altered gene who are planning a family?

Many people with an altered gene opt to have children in the usual way. Alternatively, women or men with a BRCA1, BRCA2 or PALB2 gene alteration may have the option of having Pre-implantation Genetic testing (PGT) involves undergoing the fertility treatment in-vitro fertilisation (IVF). PGT has the extra step of genetic testing of the embryos (fertilised eggs). The aim is to only put embryos into the womb which have not inherited the gene alteration. The Genetic Counsellor or Clinical Genetics Doctor can discuss this in more detail with individuals who are keen to consider this option. Testing in pregnancy is theoretically possible, but not often considered for conditions that affect people as adults.

Is there an alternative to genetic testing?

You may decide not to have genetic testing. Whether or not you are tested, you should talk to your clinician about screening options for you and your relatives.

I’ve heard of research studies involving people with a family history of cancer. How can I find out more?

There may be research studies that you are eligible to take part in if you wish. It is important to remember that research studies may not benefit you directly but may help future generations.

How to contact us:

Gates 24A

Brunel building

Southmead Hospital

Westbury-on-trym

Bristol

BS10 5NB

© North Bristol NHS Trust. This edition published March 2023. Review due March 2026. NBT003389